Latter-day Saint Missionaries in the Guatemala Earthquake of 1976

by Larry Richman

This is part 1. Read part 2 about the work Camp Patzicía.

At 3:03:33am on February 4, 1976, an earthquake hit Guatemala. 23,000-25,000 people died, 80,000 were injured, 250,000 homes were destroyed, and nearly 1.5 million inhabitants were left without shelter.

Read a summary of the devastation caused by the Guatemalan earthquake of 1976.

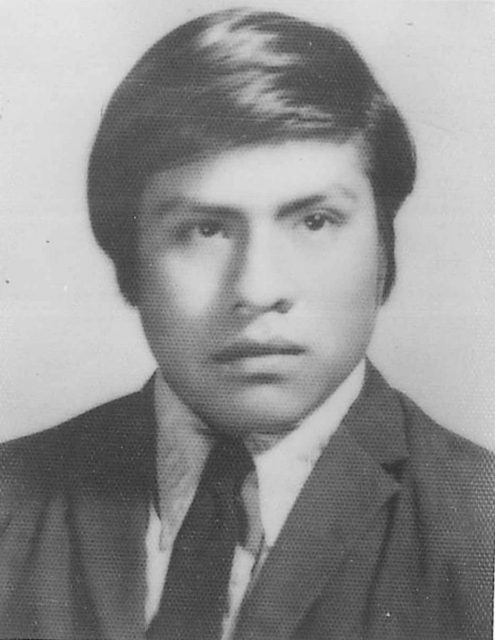

Missionaries in Comalapa

I was a missionary serving in the Guatemalan town of Comalapa. My missionary companion, Elder Gary Larson, had joined several other missionaries in the nearby town of Patzicía to learn the Cakchiquel language spoken by the people in this area. I stayed in Comalapa to do missionary work with Eber Caranza, a 19-year-old member of the Church from the nearby town of Patzún. Tuesday night after a full day of missionary work, we went to bed expecting a good night’s rest.

At 3:03:33am, Wednesday, February 4, 1976, Mother Earth let all hell break loose with a 45-second earthquake that measured 7.6 on the Richter scale (90 times stronger than the earthquake that leveled Managua, Nicaragua in 1972). The wall by the side of my bed gave way and about 200 pounds of adobe covered my bed, wakening me from my sound sleep.

Inside our apartment in Comalapa after the quake. Eber’s bed is on the left. My bed is on the right. (The blankets at the foot of my bed are barely visible. The ceiling caved in after we left the room.)

At first, I thought it was a dream. I couldn’t believe that I was actually lying in bed trapped, unable to move my arms or legs. The earth continued its horrible convulsions and more dirt began to fill my face. This made me quickly realize that it wasn’t a dream, and that if I was to live through this, I must get out fast! I soon freed one hand and with it pushed away the dirt that had covered my face. I thrust my hand upward waving it frantically and shouting for help.

Eber answered my call from the other side of the room. I pushed and finally freed myself from the blankets that held me prisoner, and slid out on the side of the bed that wasn’t covered with adobe. I looked in his direction and could see him faintly by the moonlight shining through the hole left by the fallen wall on the other side of the room. We found each other, and hand in hand we scrambled for the exit, climbing over his bed and out the hole in the wall.

View from the inner patio. The pink wall on the right is the outside wall of our room. On the far right are white doors that were jammed shut, so we crawled out the hole in the wall to the left of the doors to escape to the inner patio. The green room on the far left is the neighbor’s kitchen; their wall having fallen into our patio.

Once outside of our room, we ran along the covered walkway (to the right in the picture), then down the steps into the garden. The earth began shaking again and caused us to fall several times before reaching the garden. Behind us, we could hear walls giving way and the roof crashing to the ground.

We ran for the largest tree in the patio and held tight to its trunk. When the earth stopped shaking it was deadly silent. We shook our heads, dazed by it all, and still wondering if we were dreaming or if this could be reality. Then out of the silence we heard a distant rumble which grew ever louder as if a freight train was headed our way. But what approached was much more destructive than a freight train. The earth began shaking again violently and the rumble grew to an almost deafening roar. Whatever was left standing after the first upheaval of the earth now came crashing down. The shaking stopped, the roar quieted to a rumble, then the rumble hushed to silence.

There we stood in the garden in our pajamas with bare feet in the wet grass, shaking from the cold and also from fright. High adobe walls surrounded the garden, and the fallen house blocked our way to the street. We couldn’t leave the garden, nor dared we. There was a canyon several hundred feet deep just a block from our house and with each succeeding tremor, we could hear more of the cliffs around it cave in. See map.

Neighbors near and far began crying over dead husbands, wives, children, and parents. And for the next hour, over the moaning we could hear the blood-chilling sound of someone chopping away at a large wooden post that pinned his loved one.

When it finally got light enough to see (about 5:30am), we carefully approached the house to grab pants and shoes and find a way out to the street.

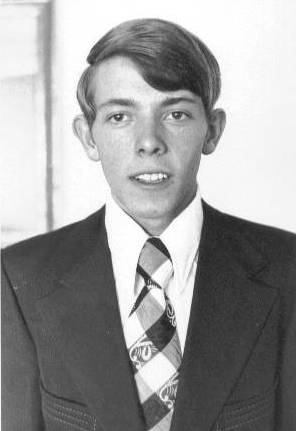

Larry Richman about 3 hours after the quake, standing in front of Walter Matzer’s room (our landlord), two doors down from our room.

Eber in front of our room in Comalapa reenacting how we quickly grabbed clothes and went out into the street. I am taking the picture standing in the street while my companion, Eber Caranza, stands in front of our room. The wall fell toward the street. The calendar hanging on the pink wall is at the head of my bed.

Members in Comalapa

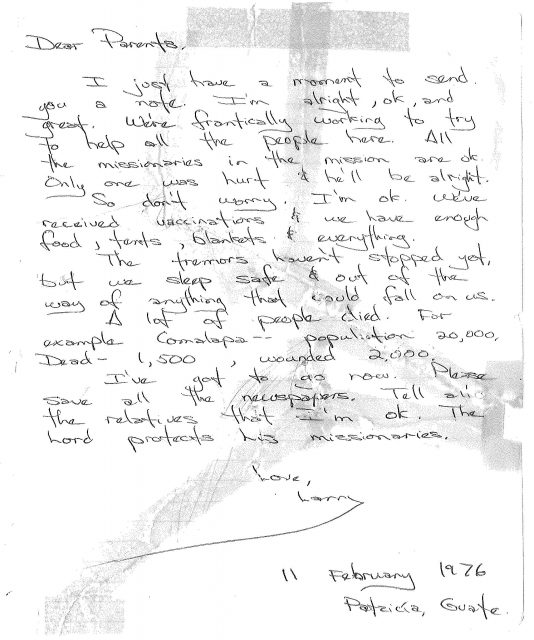

As soon as we dressed, we headed straight for the home of the Misa family. On the way, we passed countless people who called to us for help or sympathy. When we arrived at the Misa’s home, we were grateful to find them safe. The Misa family had been baptized just 12 days earlier as the first members of the Church in the town. (Learn more about the Miza family on the Comalapa page.) They stumbled out of bed and knelt in prayer in the center of the room as the house shook. The heavy adobe walls fell in all around them but none of the family was injured.

The Miza Family (Elena, Rigoberto, Hugo, and Noe) standing in front of their house after all the rubble had been removed.

Car crushed by the weight of the adobe walls.

Gathering and Organizing our Forces

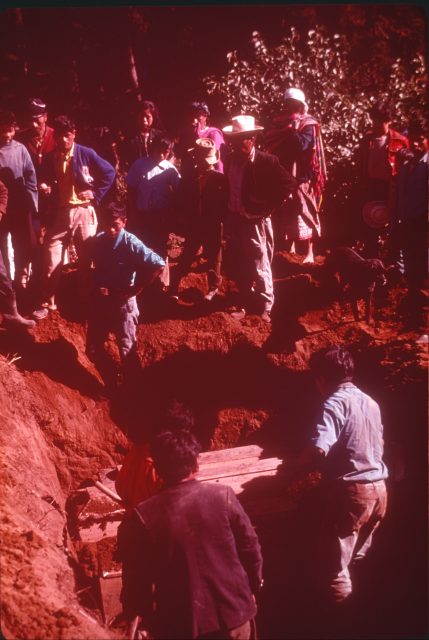

While at the Miza’s, someone made an announcement over a loud speaker asking everyone to remain calm and gather in the central plaza to organize ourselves to take care of the things we needed. Since there were 3,200 to 3,500 dead of the town’s population of 25,000, crews were organized to handle the burials.

Other crews were organized to look into sources of food and clean water. However, the most immediate need was for medical help, since there were thousands of critically-injured people and not one doctor or nurse in town.

Since quakes follow along fault lines, I realized that there could be a nearby town that had not been hit as hard as Comalapa had been hit, and perhaps they could offer us medical aid. We felt that the most useful thing we could do was to offer to go to another town to try to get aid. Being that the mayor and his family were buried alive in their house, there was a bit of confusion, but we finally got a letter from the acting mayor asking the governor in Chimaltenango for help.

Heading Out of Comalapa

Since we could not find a horse or a motorcycle, we headed out on foot about 9:30am. The winding road out of Comalapa is cut out of the side of the mountain, and the shoulders give way to steep cliffs that descend hundreds of yards. As we walked along, there were still many tremors, and parts of the dirt road would break off and slide down the cliffs. About 10:00am, we caught up with a couple who were also headed to Chimaltenango to find their son, so we traveled with them. On the way, we passed a few people headed in to Comalapa and heard from them that the surrounding towns had been almost totally destroyed as well. We also heard reports that a missionary had died in Patzicía.

As we were walking out of Comalapa, parts of the road were still breaking off and sliding down the cliffs.

We walked or ran the whole way with the exception of the last few miles when we got a ride in a jeep that had tried to make it to Comalapa but was forced to turn back because the road was impassable.

At noon, we arrived at the town of Zaragoza. From there, it was one direction to Chimaltenango and the opposite direction to Patzún, Eber’s home town. Since it appeared that Chimaltenango would not be in a position to offer us any aid, we made a decision to go to Patzún so Eber could find out about his family. We gave to the couple we were traveling with the letter from the town of Comalapa asking for medical help, and asked them to deliver it to the governor in Chimaltenango. From Zaragoza, we walked another few miles before we got another ride that took us as far as the town of Patzicía. Our hearts sunk as we neared the church in Patzicía and found it almost completely destroyed.

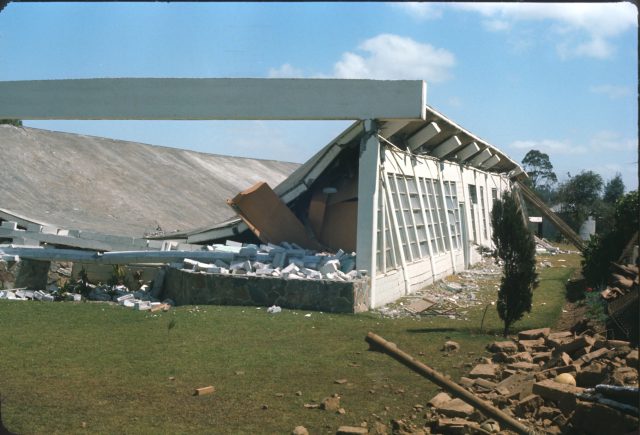

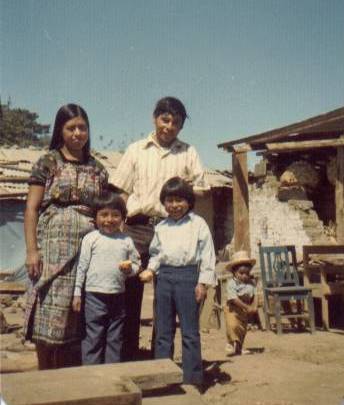

Patzicía Church

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Patzicía is visible from the highway. As we approached it, we could see that the church made of cement beams and cinderblock was totally destroyed. Although the classrooms along the side of the building were still standing, the roof over the chapel and the cultural hall had collapsed to the ground.

Church in Patzicía from the cover of the Church News. Quotes below are from that article.

“The quake caused the Patzicía chapel roof to slide backward about three feet, thus tipping over the massive reinforced concrete beams that supported it. As these beams toppled on their sides, their own weight was too great and they broke in the middle, dropping the roof in two nearly intact pieces into a V-shape. The only area standing is the classroom wing on the north. This, also, is heavily damaged.” Read more details in these articles in the Church News.

Inside the chapel. Looking toward the left side of the podium. The piano on the stand is barely visible as the beam stopped just short of crushing the piano.

Back of the church in Patzicía, Guatemala after the earthquake of 1976 (Photo courtesy Michael Morris)

Missionaries in Patzicía

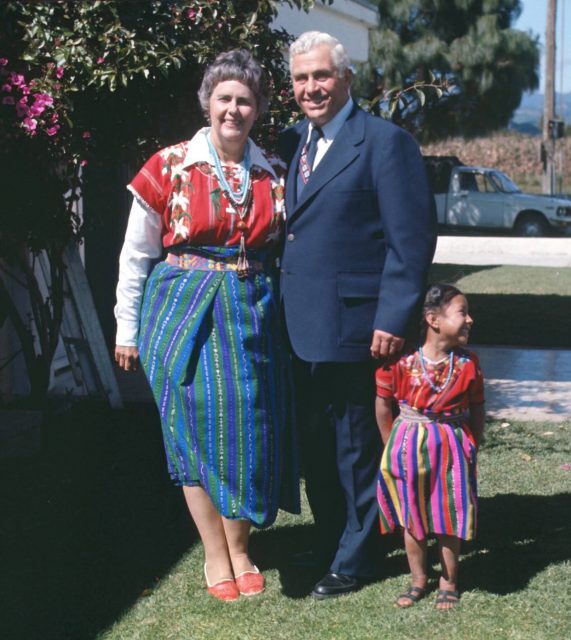

Senior Agricultural Missionary Couple

Elder Bleak Powell and Sister Gladys Powell in a native blouse and skirt in 1975 by the church in Patzicía, Guatemala before the earthquake.

Elder Bleak Powell and Sister Gladys Powell were agricultural missionaries, living in one of the classrooms at the church. Of their experience, Sister Powell wrote: “Around three o’clock in the morning we were awakened by the shaking of our bed…. The shaking became more violent…unbelievably violent! We could only try to hold on to the bed. We could hear the furniture and our personal belongings being thrown about the room. It was as if a huge giant had the chapel in his hands and was angrily shaking it. Suddenly we could hear the building breaking and crashing over us! The noise was deafening. Then the horrible shaking stopped, almost as abruptly as it had started. We stumbled out of bed and over the rubble and into the hall. Then we saw the grotesque pile that once had been the chapel and recreational room…the whole opposite side of the church had fallen!” (Excerpts from February 4, 1976: We Were There, an unpublished account by Gladys Powell.) Read their five-page story “February 4, 1976: We Were There.”

View from the back of the Patzicía church. The Powell’s room was in the back right corner of the building.

Sister Powell wrote: “As long as I live I shall never forget the sounds that began to arise from the people. We could hear the wailing and weeping as the people began to pull their families from under the piles of fallen adobe. Their homes were deathtraps, for the adobe was only mud and crumbled to crush and smother them. When daylight came, I could see that the home of our next door neighbors was destroyed and I could hear the weeping of the women, so I climbed over the mounds of rubble into what had been their yard. Their little eight or nine year old boy was walking around in a daze, carrying the body of his little dead sister in his arms. I put my arms around the mother and tried in my feeble way to comfort her, telling her that we have to be strong when things seem hopeless and that we have to have faith. She thanked me and softly said, ‘It is God’s will.’

“Many of the Indian brothers started coming to see if we were safe. One said, ‘Sister, President Choc’s wife and two little sons were killed.’ Another came saying that the Relief Society President and her baby were dead.” (Excerpts from February 4, 1976: We Were There, an unpublished account by Gladys Powell.)

Elders in the Language Class

Several missionaries had been staying at the church taking the Cakchiquel language classes I mentioned earlier.

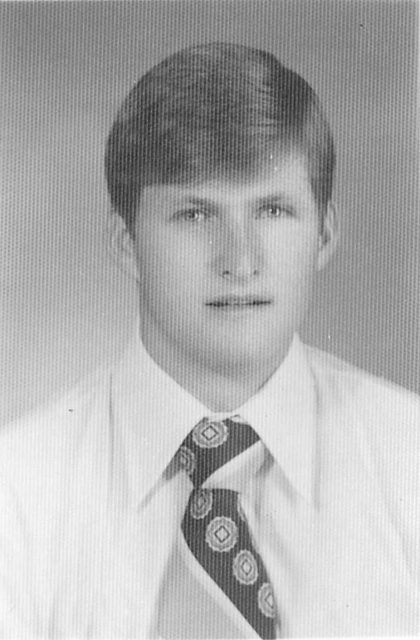

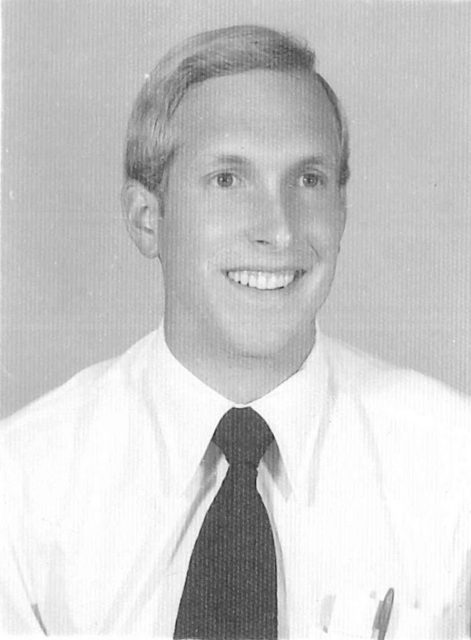

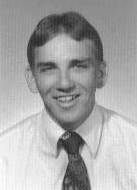

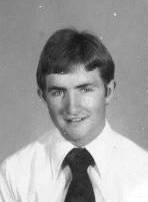

Elders Gary Larson, Steven Schmollinger, and Fred Bernhardt had been sleeping in a little adobe house just outside the fence of the church grounds. They were spared injury because the walls of the house fell outward and the gabled roof fell over their beds.

However, two other missionaries, Elders Randy Ellsworth and Dennis Atkins, had slept that night on mattresses on the stage in the cultural hall of the building.

During the earthquake, the roof of the building gave way and one of the large 50-ton concrete beams descended and landed on Elder Ellsworth’s back, pinning him to the wooden stage. Another beam fell on Elder Atkins’ pillow, but fortunately the violent shaking had thrown him from the mattress and he escaped injury.

Stage at the Patzicía church where Elder Ellsworth was pinned. See another photo and another.

These missionaries, along with members who arrived later, worked heroically through the black of night to free Elder Ellsworth. When more tremors came and bricks began to fall around them, Elders Evans and Salazar blessed the walls that they would not fall until Elder Ellsworth was rescued. They worked with crude tools for six hours to cut the stage out from under him.

When they extracted Elder Ellsworth at about 9:00am or 9:30am, they put him in the bed of the Powell’s small pickup and headed for the hospital in Guatemala City. Eber and I arrived in Patzicía about a half hour after the pickup left for Guatemala City. Elder Ellsworth was later flown to a hospital in Panama City, and then to the United States (see article

1 and 2) where one miracle after another saved his life and his legs. Six months later, he later returned to Guatemala to complete his mission. Read “I’ll Stand and Preach the Gospel.” See letter by President O’Donnal explaining Randy Ellsworth’s story.

See the following talks in General Conference that relate information about Elder Ellsworth’s experiences:

- Thomas S. Monson, Ensign, Nov. 1976, page 53

- Marion G. Romney, Ensign, Nov. 1977, page 42

- Thomas S. Monson, Ensign, Nov. 1986, pages 41-42

In a letter to President John O’Donnal 21 years after the ordeal, Randy Ellsworth wrote the following: “I feel I owe a great debt to the people of Guatemala and the missionaries who sacrificed so much in risking their own lives to save my life…. I am always given the credit for what happened in the earthquake, but in reality I only awakened to find that a beam had fallen on me. It was the other missionaries and the brothers of Patzicía that, being safe and sound, risked their lives crawling to where I was, sure that I was going to die regardless. When a second tremor came, without hesitation, one of them raised his arm to the square using the Melchizedek Priesthood, blessed the walls that they would not fall until I was rescued. They are the ones who deserve the credit and I do not want to betray them. For me the elders and the brothers of Patzicía are the true heroes.” (Pioneer in Guatemala: The Personal History of John Forres O’Donnal, Shumway Family History Services, Yorba Linda, CA, pp. 130-1.)

Language Teachers

Elders Salazar and Evans, the language teachers, were living in the missionary quarters in the center of town. Elder Taz Evans wrote the following: “The moment the earthquake hit, we were snatched from our beds and pulled outside. There is no doubt that it was a miracle and that we were removed from the house before any danger could befall us. Outside we kneeled and had prayer, taking turns to pray aloud. We blessed the walls of our fallen room by the power of the priesthood, then crawled back to search for our flashlights and to get some clothes before running out to see what we could do.” (Pioneer in Guatemala: The Personal History of John Forres O’Donnal, Shumway Family History Services, Yorba Linda, CA, p. 148.)

The Elders made their way to the church and assisted in the heroic efforts to free Elder Ellsworth.

Missionaries in Sumpango

“Elder Daniel Choc, son of Pres. Choc, and Elder David Frischknecht were in Sumpango. Every home on their street was a mass of rubble, except theirs. It held, and the elders were not injured.” (Church News)

Missionaries in Patzún

The missionaries in Patzún were Elder Garth Howard and Elder Luis Manuel Argueta.

22 Latter-day Saint Members Killed in Guatemala Quake—15 in Patzicía

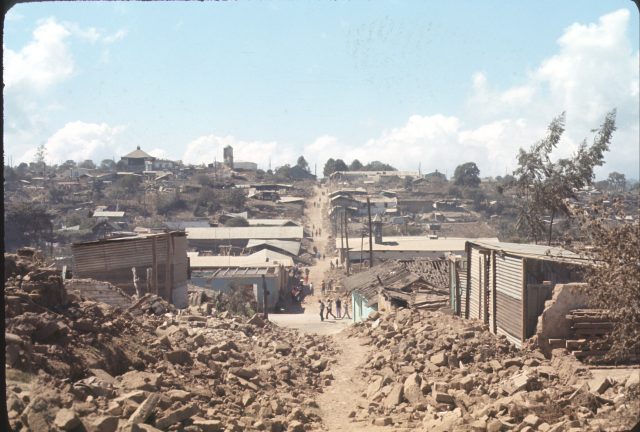

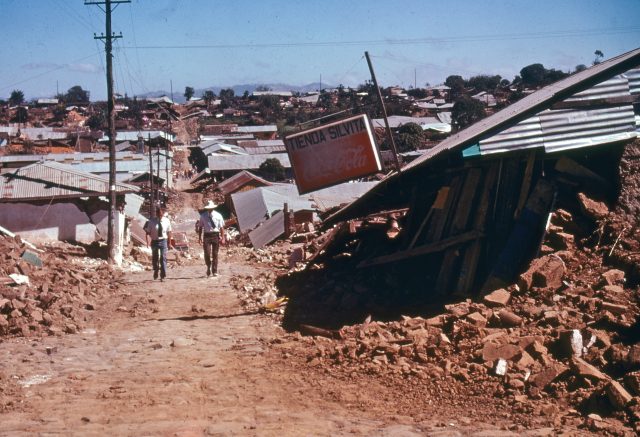

Patzicía, Guatemala, days after the earthquake of 1976. Elder Frischknecht on the left (Photo courtesy Michael Morris). See more street scenes: 1 and 2

Fifteen members died in Patzicía, including the pregnant wife and two of the smaller sons of Pablo Choc, president of the Patzicía Branch. “Most of the members died in the rubble of their homes in the villages of Chimaltenango and Patzicía, about 40 miles north of Guatemala City. Most of the homes destroyed were small, adobe houses. With the first hard quake, they collapsed on the sleeping families taking a heavy death toll.” (Church News)

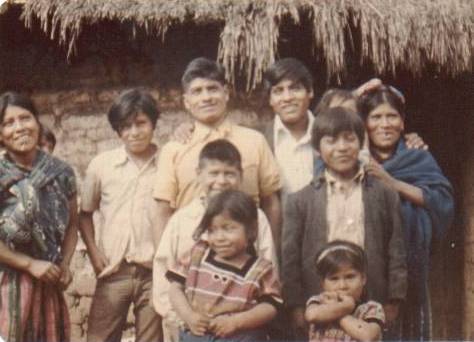

Pablo Choc family before the earthquake at Elder Daniel Choc’s missionary farewell. See alternate photos 1, 2, and 3.

See the Patzicía page for more photos and information about the Pablo Choc family.

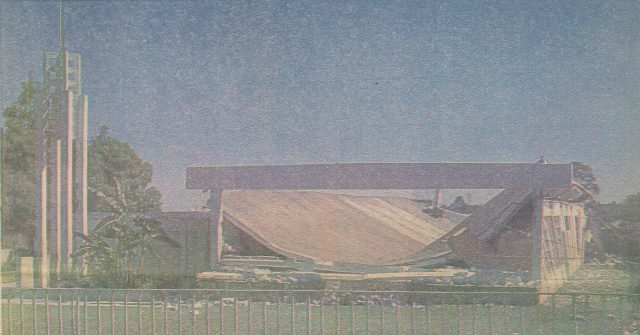

It wasn’t just adobe that came tumbling down. The Catholic cathedral made of brick and mortar in the town square in Patzicía, Guatemala, was also broken into pieces.

Cathedral in the Patzicía, Guatemala town square days after the earthquake of 1976 (Photo courtesy of Michael Morris)

Elder Richman sitting on the remains of the brick-and-mortar tower of the cathedral in the town square in Patzicía, Guatemala.

Continuing on to Patzún

Eber and I continued on to Patzún to see his family. Just outside Patzicía, we got a ride in a truck that took us a few miles until the road became impassable. We then walked until the road became impassable even on foot. Since Eber grew up in the area, he knew of a trail through the woods, so we backtracked until we found the trail and took it to Patzún.

Photo of the municipal building in Patzún taken days later, after the rubble on the street had been cleared. Elder Daniel Choc is standing in front.

When we arrived in Patzún, we found about the same devastation as in the other towns, but found that Eber’s family was all right.

I left Eber with his family and spent the night in Patzún with Elder Kelly Robbins and Elder D Warnock. Since we didn’t want to sleep near any buildings, we slept on the hillside just above the house where the missionaries lived. There were tremors throughout the night and we got very little rest.

Returning to Patzicía

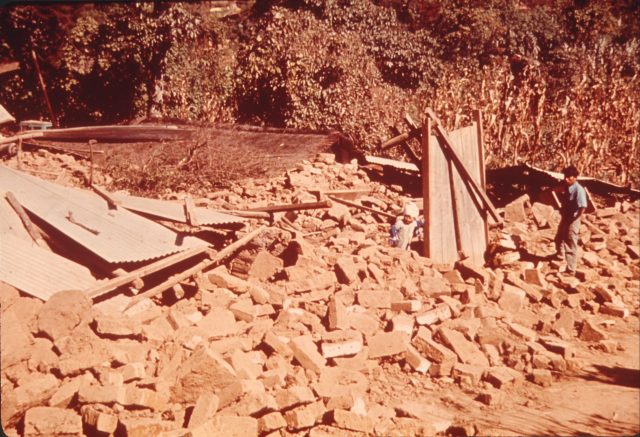

Thursday morning, February 5, we returned to Patzicía. I admired the courage of the branch president Pablo Choc, who was burdened with the responsibility of 325 members, some of whom were injured and all of whom were homeless. The branch Relief Society president Arcadia Miculax was dead. Pablo’s own wife was killed in the earthquake along with two sons. He was left to care for seven children, the oldest of which was Elder Daniel Choc Xicay, a missionary then serving in the nearby town Sumpango. That morning we buried President Choc’s wife, his two sons, and twelve other members of the branch in a single large grave. I dedicated the grave at President Choc’s request.

That night, our mission president Robert B. Arnold came with rolls of heavy plastic to cover our sleeping bags and make temporary lean-tos for the members as temporary shelters.

President Arnold instructed us that our primary responsibility was to help the members with their immediate needs, and he asked me to stay in Patzicía. I was glad to be of service to the members in Patzicía, since I had worked in the town for almost nine months previously and knew the members well. Nevertheless, I felt a responsibility toward the town of Comalapa where I was assigned at the time of the earthquake. There was only one member family, and they were all right, but I felt that the rest of the town also needed our help and might feel that we had deserted them.

Returning to Comalapa

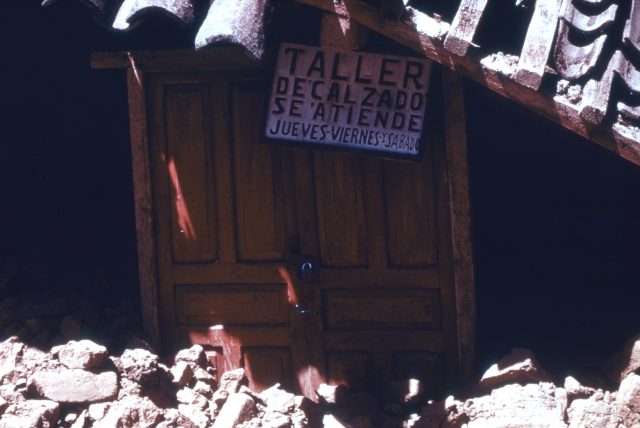

Friday morning, February 6, we returned to Comalapa to get our personal belongings since the wall in our room had fallen in the earthquake and the room was exposed to the street. By then, the road into town had been cleared and in places they had cut new roads through farmers’ fields. We found that there was even more destruction in Comalapa than there had been at 9:30 the morning after the earthquake when we had left the town, since more had fallen during the tremors Wednesday and Thursday. I wondered if the town would rebuild or if it would turn into a ghost town.

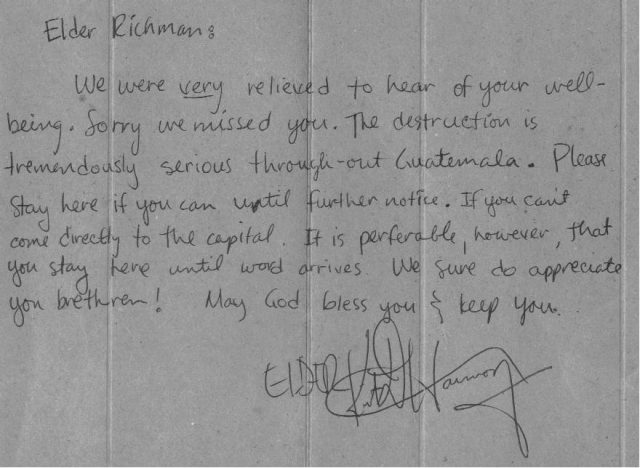

At our house in Comalapa, we found a note left by the zone leader, Elder Kirt Harmon. Read a story by Elder Kirt Harmon, published in the January 1979 Ensign that explains how he and Elder Daniel Choc went to Comalapa to check on us. (See a PDF of the story.)

A parent’s concern

It was many days before I could get word to my parents that I was all right. The day of the earthquake, my parents were able to talk with President Arnold’s wife on the phone and she assured them I was all right (even though the mission home hadn’t yet made contact with us). Nevertheless, my parents were anxious to hear from me to be sure. Dad sent five letters until he finally received one from me. The following is an excerpt from his letter dated Sunday, February 8, 1976:

Dear Larry,

These have been most anxious days for us this past week, watching the news and searching the newspaper. Our prayers are with you and your loved ones there. We pray for your welfare. We wish we could help. It was a relief to talk to the wife of your mission president, Sister Arnold, and she assured me you were okay, as well as Elder Luis Manuel Argueta. We know that this must be a heart-rendering experience for you as you help God’s children and as you exercise your priesthood, that many testimonies will grow, including your own. Our thoughts and our prayers are for you constantly. We know how much you love the people there.

We are still anxiously awaiting word from you. We pray that you are getting enough to eat and water to drink. We hear all kinds of stories of starvation and epidemic conditions. As soon as you can, write, telegram, or call us. We love you so much and know that you are really busy. Please let us know how you are as soon as you can. We pray that all of our Father’s choicest blessings will be with you and the members there.

All our love, Dad

On February 16, he wrote, “We hope you are well and that things are starting to get back to normal. We are still anxiously awaiting word from you. Please call, telegram, or write and let us know how you are.” (The last letter he had received from me was January 27.)

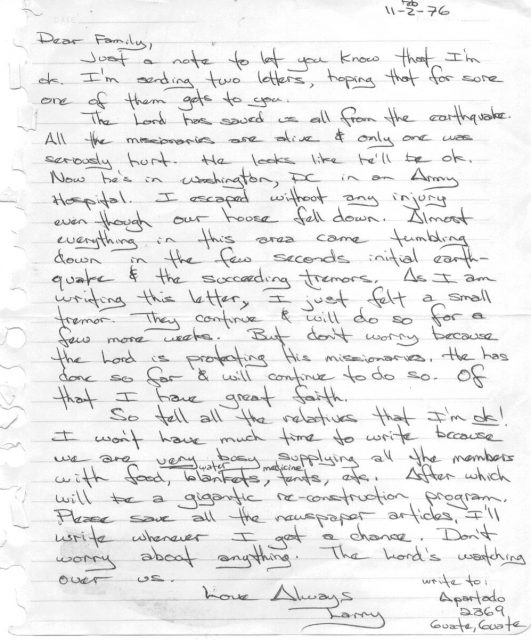

I couldn’t call or telegram, because the lines weren’t functioning. The following two letters dated February 11, 1976 are two of many letters I wrote home, hoping that at least one of them would make it.

One of these letters arrived in Boise on February 17. Dad wrote me back the next day, saying “We received your letter yesterday dated Feb 11th. You don’t know how relieved we are to hear all is well with you. We know our Father in Heaven is protecting you, but we were still anxious to hear from you.”

Read an article from the Idaho Statesman newspaper about the earthquake and a report on Elder Richman.

Relief came quickly

Missionaries assisted in distributing food, clothing, and blankets, as well as pots and pans for cooking and boiling water. Doctors and health missionaries arrived to give injections to prevent hepatitis and typhoid. We feared widespread epidemics because of the contaminated water supplies and also because they were still digging dead bodies out of the rubble several days after the earthquake. The stake in Quetzaltenango immediately sent carloads of supplies, and soon additional help arrived from the Church in Salt Lake.

Sister Cathy Hyer gives injections of Gamma Globulin and typhoid vaccine to people to prevent widespread disease. Elder Richman assists.

People began to clear out the rubble with their hands and hoes. Within a few days, big machinery arrived to begin to clear the streets.

Continue to part 2 of the story “Latter-day Saint Missionaries in the Guatemala Earthquake of 1976.”